It’s probably better to overestimate the threat of conflict

in international affairs than to underestimate it. But it’s certainly better to dispense with

alarmist assessments if you can make more accurate ones.

Ask anyone who follows international affairs where the

hotspots in Asia are right now and that person will be quite likely to bring up

the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands dispute between China and Japan. We heard an informative presentation by Mr.

Daniel Hartnett at last weekend’s fall conference on the matter in which it was

predicted as being “likely” that a skirmish will occur between

China and Japan and potentially lead to war.

National pride and the desire to exploit possible sea floor oil deposits

have caused tensions to rise over the last few year and most informed people

see a tipping point looming on the horizon. But consider the incentives all

nations involved have to avoid war and it’s rather obvious that violence isn't

even close to likely.

Distorted assessments like these are often created by a lack of

important information about the capabilities and interests of the parties to a

dispute. The Team B Report from 1976,

for example, took advantage of American ignorance of the USSR. With a dearth of reliable information, its

assessment was driven by ideological goals emphasizing the possibilities for

conflict instead of its probability.

But in the East China Sea we have a tremendous amount of

information to give context to our assessments.

The values of the three main parties to the dispute – China, Japan, and

the U.S. – are well understood and we can see them choosing to behave rationally

to avoid conflict.

Undoubtedly, there are plenty of people in China who would love

to go to war with Japan – riots occurred in Chinese cities after Japan

purchased the islands from one of its citizens and nationalist Japanese sojourned

to the Senkakus to wave the Rising Sun.

But in China, the government runs the show no

matter what – what regular people think doesn't matter in the formulation of

foreign policy. After initially seeming to encourage the protests, Beijing put

the clamp down to calm tensions. This

has been in keeping with the recent trend in Chinese foreign policy to stop

trying to scare the wits out of its neighbors through saber rattling and

instead grow its soft power in the region and throughout the world.

Conversely, Japan is a democratic society that is staunchly anti-military. If shots are fired, it won’t be Japan who

does it first, as it is forbidden from initiating aggression by Article 9 of

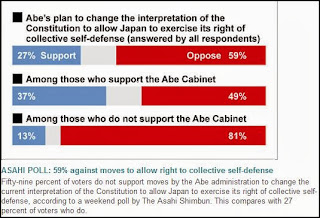

its constitution. There have always been

nationalist elements who would like to reinterpret Article 9, but they remain a

minority according to an August, 2013 poll by the Asahi Shimbun:

The U.S. itself has every incentive to prevent violence

breaking out, as it is obligated by security treaty to come to Japan’s defense. And, of course, Japan and China are two of

the United States’ largest trading partners.

In today’s liberal international framework, nations no

longer view war as the best path to economic riches and political power. Particularly for Japan and China, no matter

how deep the historical enmity, one huge factor will maintain peace: economic

interdependence.

To quote the New York Times at length on the issue:

According

to Japan’s Finance Ministry, China was Japan’s largest trading partner last

year, and Japan is China’s second-biggest trading partner after the United

States. Japan is also China’s largest outside investor, with Japanese companies

directly or indirectly employing about 10 million Chinese, according to a

Japanese lobby group.

Perhaps

as important as the volume of the trade and investment, though, is how

complementary the two countries’ industries are.

Japan’s

still formidable lead in technology allows it to provide much of the production

machinery in Chinese factories and many of the core components in Chinese-made

products that have helped make China’s rise possible. Japan’s struggling

electronics companies, in turn, have become dependent on sales to China’s

lower-cost manufacturers, which use Japanese memory chips, display panels and

other parts in many of their high-tech products.

Both nations want to exploit any oil-deposits around the

Senkakus for economic gain, but realize that war to achieve that goal would

first result in economic suicide. Japan

is an established liberal democracy and China’s political development seems to

have matured enough to recognize such costs of war and benefits of peace. As Mr. Hartnett posited, if tensions turn to

violence it would most likely not start from official command, but from a

Japanese or Chinese captain carried away by patriotic fervor. So the question is really how committed and

able the Chinese and Japanese governments are to preventing hot headedness.

Of course, it’s difficult to know how strictly enforced the

engagement policies of the respective governing entities are with any

specificity. But my take is that these two politically mature governments

recognize the costs of a skirmish and know that providing clear directives to

their respective maritime forces is of utmost importance.

So when the incentives of all three parties are taken into consideration it’s obvious that predictions of war really are alarmist. What’s most likely is that China and Japan will cool tensions and shelve the Senkaku issue to focus on those that are of much greater importance to their economic securities. And if things really do start to grow out of control, the U.S. will use its hegemonic influence to press for an internationally mediated resolution where both sides can find victories to claim. All involved are smart enough to see that their larger interests are better served by negotiation than war.

No comments:

Post a Comment