Thursday, November 30, 2006

Response to "Call it what you want"

According to what seems to be the popularly held political science definition, a civil war requires (1) that there be warring parties from the same country fighting for political power or seperatist state and (2) at least 1000 people killed with 100 from both sides.

There is no disputing (2). It's riduculous to argue over what body count causes bells to ring, trumpets to blow and big balloons to drop down from the sky while a biplane spells out "Civil War" in the sky.

But (1) is where the Bush administration - and anyone else - has some room to debate.

In order to consider the situation in Iraq a civil war, you have to assume the existence of a real country. The details of the formation of Iraq is not exactly a story that inspires confidence.

Because of the way Iraq was created, because of the volatile mix of Sunnis, Shias and Kurds, there is still dispute over who the players are. It isn't just insurgents, fighting against a US-backed government. It isn't just Shias and Sunnis, fighting a civil war over religion. It isn't just Kurds, fighting for a seperate state. It isn't just Iran, Al-Qaeda or the US. It's a lot of things at once.

What are all these sides fighting for? Oil? Land? Sovereignty? Religion? Democracy? The new Caliphate? Intifada against the Zionists?

I understand the reluctance to call Iraq a civil war, like I understand the reluctance to call America an empire. But there is no other terminology. But in the case of Iraq, as in the case of America, the definitions are being changed to fit the situation; not the other way around.

The hesitation to call Iraq a civil war is more than just PR. The term

"civil war" recognizes a lack of control, and dramatically changes the interpretation of the US role in Iraq.

Says one columnist:

"This matters. We not only speak, but think, in language. To communicate effectively, we must describe things efficiently. Agreeing upon its name is essential to a deeper understanding of any phenomenon. Nouns are the handles with which we grip reality.

Our troops can kill our enemies no matter what we call them, but our inability to describe our experience in Iraq accurately makes it far harder for our civilian leaders to understand it. (Not that everyone in either party is committed to an honest analysis.)"

Regardless of what we call it, there is war and killing and Iraq. There will probably be, as Profarley says, genocide on the horizon. And not the kind the UN can ignore.

There is a civil war in Iraq. America is an empire. This is an empire, and a civil war, that have never been seen before. We need to expand the definition, debate it and discuss it. Make it into something we can grasp, so that we can move forward in addressing what is indisputably going to be remembered as the most significant war of the 21st century.

Tearing Kim Down, One 80's Legend at a Time

When you read Resolution 1718, you hear the Security Council crying out to the world; just read the opening words of the declarative section: “Recalling, Reaffirming, Expressing the gravest concern, Expressing, Deploring, Deploring further, Endorsing, Underlining, Expressing” That’s three ‘Expressings’ and two ‘deplorings--’ you can’t find that kind of angst this side of a My Chemical Romance show.

The UN has done it’s part. Now it’s left for the State Department to make sure the Commerce Department puts rules in the Federal Register to be enforced by the Customs Bureau who is owned by Homeland Security. Marvel, if you will, at the incomparable speed of a furious American bureaucracy, hell-bent on stopping Kim from stealing “That’s Just the Way It Is,” “Gonna Be Some Changes Made,” and the earth-shattering "Power of Love."

Kim: you’re done for. We’re bringing the pain, baby. If you even think about touching Hall and Oates, let's just say your goofy-ass hair will be the least of your problems. After we settle the big issues of Segways and Stratocasters, we can consider the details--like oil—that is, if we have time.

(Forgive me for posting on the blog rather than replying: do you have any idea how rare it is that I can post a picture of Bruce Hornsby?)

Wednesday, November 29, 2006

Russian conspiracy and N. Korea entertainment ban

In continuation of our talk today about the suspicious death of the Russian spy, Alexander Litvinenko, officials have found traces of radiation on two British Airways jets. Authorities have refused to specify if the substance was polonium, but the airline is contacting tens of thousands of passengers who were on the jets and may have been exposed. (For the record, Litvinenko was in London 11/1, the day he reported having symptoms.) What does this imply? Litvinenko was meeting with Italian securty expoert Scaramella and the two had obviously exchanged some good gossip. Could he have later poisoned his friend? Or, as a fellow class mate put it, should we note that people that Putin dislike seem to die?

Anyone else see that the US has now banned the sale of iPods, plasma tvs, Rolexes, yachts and other luxury items to North Korea? Apparently this is the first effort (being coordinated under the UN, too) to designate a specific category of goods not associated with weapons or military buildups. This seems a little bizarre to me. With the connections and cronies Kim has, it seems the man could figure out how to get an iPod from elsewhere. I wonder if other nations will collaborate on this effort.

In other news, Mel Gibson has now said he is sympathetic for Michael Richards. I can't imagine.

Mahmoud Believes in Democracy

Call it want you want, but it is

While researching the different numbers and talking to various organizations as to how they arrived at their figures I realized that there is no accurate or very

reliable way to get an accurate civilian death toll figure.

The true figure probably lies somewhere between the Associated Press count of 1,216 and the U.N one. But does it really matter? The fact of the matter is that innocent Iraqi civilians are getting slaughtered in record numbers and each month it gets worse.

Why is the US still debating on whether or not to ‘officially’ call this a civil war? The civilian population of Iraq continues to be victims of terrorist acts, roadside bombs, drive-by shootings, crossfire between rival gangs or between police and insurgents, kidnappings, military operations, crime and police abuse. Please let me know where, then, civil war would be an apt term.

So while we journalists here and outside Iraq debate the politically sensitive death toll numbers and wonder about the methodology used to arrive at the different figures, does it really matter? Is there a magic number that we must reach to label this conflict a civil war? Innocent men, women and children are living under horrific conditions, isn’t that enough?

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

Blowing off some steam...replys welcomed, cause I ain't no genius

You know, all I hear from the our politicians are generalization plans, get the troops out, send more over, create a timeline,, get out in 4 months, get out when we have the job done, and on and on. It's making me a little dizzy and frustrated.

I wish the government would host a town hall style open forum, simply for the goal of educating the public as to the specifics in such plans, and more over, I wish the Bush Admin would attend. I mean, honestly Mr. President, I do respect you and the office of the Presidency, but announcing that Al-Qaeda is the biggest threat to the stability of Iraq? Who is he fooling? Even Gen. Abazaid said they're a small threat, 2-3% of the actual number of estimated insurgents. We all know it's the sectarian militias and dead squads.

I'd offer up the following suggestions to at least announce publicly so that the Am. public at least perceives of some progress: (maybe our media - God bless their shallow souls - will seek out legislatures to report on this.

Equip Iraqi army with better gear--our gear - to keep them safe. All they have is some dinky vest and bullets are scarce. We need more ADVISORS, not just troops, that have combat experience, critical to help train Iraqis so maybe BENCHMARKS can be set for a US departure, not just a timeless. I hate when throws around the word 'timeless'. I think it's a cop-out and cowardly answer.

The Admin. should be announcing Iraqi views of whether a central government would function or if partitioning the country would work for a safe and more stable country. I, personally, think the only way Iraq will gain peace is if the people are lead by their own sect. Don't under estimate the characteristics of comfortability and similarity that make for stability.

I'd like to hear more about oil money distribution and how the US would prefer to see that happen, regardless what Iraq thinks, although it should be done how Iraq wants. I think all EU and US reconstruction projects should be divided, giving 1/2 to Iraqi people. Help them form their own cooperatives to foster good citizenship, infusing the money into the country by means of local participation. Then the US won't be seen as 'just in it for the oil'. And how about training Iraqi youth in developing enterprises and small business so they’d be less likely to get snatched up by Al Qaeda and given AK-47’s at 15 years old. Where’s that being announcing in the US plan?

Finally, whenever the violence dwindles, start a massive Joe Nye soft power movement and bring 1000's of Iraqis over to the US to study and earn degrees and foster exchange programs...in the distant future, I know. Europe should no less contribute to this too.

So I hope the Dems will start getting to work. I'm still hearing a bunch of gloating from their throwns in Congress.

Ok, I feel better. Thank you to those 1-2% who actually read my venting.

Monday, November 27, 2006

Mahdi Army

I remember people talking during the Hezbollah conflict last summer about how Hezbollah should have been disarmed long ago to prevent this war. Should the Iraqi Army attempt to militarily disarm the Mahdi Army?

Sunday, November 26, 2006

The Shiite Is Hitting The Fan

Via Sully, here is a gem of a chart potraying how far we have to go towards winning the hearts and minds of the Shiite community in Iraq. It would appear that a clear majority of Shiites now support attacks on American forces, and they want the US to leave even if that causes violence to increase.

I don't think I'm giving any original analysis when I say that the Shiites wouldn't mind us leaving because they feel like they are the dominant power in Iraq. They have superior preponderance, funding (Iran), and political power (the Maliki government). The Shiite community has become emboldened in recent months as they stepped up their attacks on the Sunni community and have even begun to kidnap well-armed and well-protected contractors in broad daylight. True, it hasn't gotten to a point where they are trying such bold attacks on American military personnel, but that seems to be the next logical step.

So what can the US and allies do to fight Shiite extremists through the lens of the recent "Go Big, Go Long, or Go Home" approach? None of the options seem perfect. To "Go Big" this late in the game would have little to no effect. Iran IS the player in southern Iraq, not the US. The Iranian government has already funded the building of a train station and airport in southern Iraq. Furthermore, NBC's Peter Engel has reported that if you're booking a hotel in southern Iraq, you're doing it while speaking Farsi. To also "Go Big" would also be politically impossible as the Maliki government would never let it happen.

So what can the US and allies do to fight Shiite extremists through the lens of the recent "Go Big, Go Long, or Go Home" approach? None of the options seem perfect. To "Go Big" this late in the game would have little to no effect. Iran IS the player in southern Iraq, not the US. The Iranian government has already funded the building of a train station and airport in southern Iraq. Furthermore, NBC's Peter Engel has reported that if you're booking a hotel in southern Iraq, you're doing it while speaking Farsi. To also "Go Big" would also be politically impossible as the Maliki government would never let it happen.The "Go Home" approach also seems highly problematic. As General Abizaid recently testified, civil war is the biggest threat to Iraq, not the insurgency. To "Go Home" would allow further sectarian killings in Baghdad and greater Iraq. Not to mention a likely terrorist haven in the Anbar Province, followed by a likely Turkish invasion of the north, and Iran getting even stronger.

The "Go Long" approach, therefore, is my choice by default--the lesser of two other evils. The "Go Long" strategy might curb violence enough for the Iraqi government to decide for itself to get serious about sectarian violence. More importantly, it would likely prevent further regional chaos. I do, however, believe that it is time to set a time table. I think the time table should be set for a 12-18 months from now, and it would include the pullout of 75% of our troops. I think a deadline will do more to "incentivize" the Iraqi's to get their shit together more than anything else.

...well, guess I have to go back to spending time with my extended family. Shucks.

UPDATE:

Newsweek announces the The Most Dangerous Man In Iraq.

Surprise, surprise!!

Somehow this "important" piece does not come to one as a surprise. Actually it makes one reflect on the words of Moises Niam: "for now the trend is towards more. More trafficking, more black holes, more conflict and confusion, and borders that remain porous despite government attempts to seal them."

Saturday, November 25, 2006

Oh, a dictator and his slingshot...

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

Insanity in the Courts!!!!

I'll be flying for the Thanksgiving holiday. Let me see if I have everything I need:

1. 80k in cash....check

2. Info on nuclear plants and bombs....check

3. My 9/11/01 newspaper.....check

Looks like I'm set

A federal judge overturned a lower ruling Monday and ordered detention for a man stopped at

U.S. District Judge Paul D. Borman ruled Sisayehiticha Dinssa, 34, was both a flight risk and a danger to the community. He overturned a ruling by U.S. Magistrate Judge R. Steven Whalen, who earlier on Monday ordered Dinssa released under strict supervision.

Dinssa, an Ethiopian-born

He is charged with currency smuggling after telling Customs agents he was only carrying about $18,000 before a search of his luggage turned up nearly $80,000.

Though he faces no terrorism charges to date, Assistant

Agents found articles about nuclear plants, suitcase bombs and a hard-copy commemorative edition of the

Agents also found a hand-written note saying: “This community is angry. Something is going to happen. We are going to see justice. This is a powder keg waiting to go off.”

Now, imagine if, a couple years after, say, the Oklahoma City bombing, a twenty-something white male with a buzzcut gets found at an airport with this same stuff on him....Yeah.

But Christ alone help us if we make these guys livid over detaining a man for a couple days, coming back from the most muslim-populated part of the planet, to one of the largest muslim communities in America, with documents on suitcase bombs and nuclear weapons.

Damn, I'm just an insensitive jerk, aren't I?

Sunday, November 19, 2006

Amenable to Ahmadinejad

Ahmadinejad represents a crucial break in Iranian politics – he is the first post-revolutionary who is not a cleric he fought in the Iran-Iraq war, and crucially he is seen as not being corrupt.

If the West has underestimated his government's influence in Iraq and the region, they have also exaggerated his vulnerability here in Iran.

[...]People here feel that when it comes to Iraq and even Lebanon and Afghanistan, Britain and the US need them, not the other way round.

What they want to know is what benefits does Iran get for such assistance?

An interesting proposition. After all, we do make a great deal about the difference between Iranians and Arabs, Iran's influence in Iraq, and Iran as a powerful figure in the Middle East feared by the other nations. Unfortunately, our close ties with Israel may complicate any attempt to develop a closer relationship with Iran...but I guess that's one of the challenges of diplomacy. Ahmadinejad, for all his unpopularity, is a different kind of leader than Iran's had in a while. Working with him, in one way or the other, would be a chance for the US to cooperate with a large and powerful populations of Muslims in a crucial region in the Middle East.

It's tempting, even if it is unlikely. What would be the costs/benefits of warming up to Iran, in Iraq? in Israel? in the UN? in Europe? concerning Iran's nuclear ambitions?

We've cooperated with much worse figures in the Middle East before...perhaps this is a good time to rethink this realism thing after all. Iran is a powerful nation in the Middle East...and overlooking ideology and religion, it is theoretically possible to use them as a way to balance the region...perhaps between Iran and Israel?

Update: 11/20

For those who had a chance to catch Ted Koppel's "Iran: The Most Dangerous Nation", the attempt was made to explain what Iran and the U.S. have in common. On the issue of Middle East stability and the desire for democracy in Iran, the sentiments are unanimous. Koppel's interviews with various liberal government officials, shopkeepers, rural citizens and urban city dwellers all yielded the same response: Iranians would like a more democratic society, but they would like to enact their democratic reforms from within. Iranians would like to work with President Bush, providing he will stop labeling them as terrorists or part of the "Axis of Evil". Many Iranians interviewed sympathize with the Americans, believing that they too suffer from a populist leader, ignorant of world affairs and committed to pursuing a heavily religious, moral agenda.

Well and good, but the tension between the U.S. and Iran lies in what Koppel did not ask about - U.S. support for Israel - along with the citizens and officials he did not interview - those with a more hard-line bent.

Still, it will be hard to imagine a viable Middle East strategy that does not include greater dialogue with Iran, and specifically, with the Iranian people. The argument can still be made that U.S. strategy in Iraq is working - whatever that strategy may be. But there is no sensible way to argue that the same tactic of military occupation followed by forced democratization will "liberate" Iran from the more radical Islamic-theocratic elements. The U.S. needs a different tactic for Iran, and it needs to involve dialogue with Ahmadinejad and the Iranian people.

Saturday, November 18, 2006

If It Ain't Broke...

The same logic that says an understanding of foreign policy is essential to an informed citizenry can be repeated for almost any aspect of human knowledge. Doctors balk at Americans’ lack of medical training; librarians cringe because I still, as a grad student, don’t give a damn about the Dewey decimal system; and any decent mechanic will laugh at the sad frat boy who can’t change his flat tire.

The same logic that says an understanding of foreign policy is essential to an informed citizenry can be repeated for almost any aspect of human knowledge. Doctors balk at Americans’ lack of medical training; librarians cringe because I still, as a grad student, don’t give a damn about the Dewey decimal system; and any decent mechanic will laugh at the sad frat boy who can’t change his flat tire. The fact of the matter is that the volume of human knowledge has increased exponentially in the last 50 years and we can’t all be expected to know everything, or even the fundamentals of everything. Who among us can skin a deer (unless you’re from eastern

And so we study foreign policy, the bastard son of a wild party featuring history, political science, law, anthropology, and business. What we study is interesting and essential to us, but far from necessary or even enjoyable to the average person; they don’t care and their apathy is none of my concern. Just because it is important to us doesn’t make it important to them. No mechanic loses sleep because I don’t care how my carburetor works; why they hell should I care that he doesn’t know much about the Sunni Triangle?

The only time this comes to a head when the question is asked: should an uninformed citizenry be allowed to vote? Who cares—there is no possible way to stay savvy on the wealth of problems that confront the modern

And I would have gotten away for it too, if it hadn't been for you meddling kids and your firm grasp of transnational collective-security!

I really think Displayname and the excellent piece from the Brookings Institute raise a good point - is it possible to create and sustain an American electorate better informed about foreign policy?

I really think Displayname and the excellent piece from the Brookings Institute raise a good point - is it possible to create and sustain an American electorate better informed about foreign policy?I say "create and sustain" because I think it's one thing to talk about a public that informs itself around election time, and another thing to talk about creating a culture of individuals that continually inform themselves about foreign policy. Personally, I think it is a citizen's duty to do so.

I'm struck by former NSA Brzezinski's comment. I'm of his original opinion, that foreign policy has become inaccessible to the average citizen. But I don't believe that the trend is irreversible.

Before WWII, foreign language education in the United States was almost nothing. The methdos of foreign language instruction followed the method of Latin, translating text word by word with no regard for meaning. It took Pearl Harbor and war with Germany to get the US Government to set up the educational standards and programs that have made it possible and mandatory for students to have at least some understanding of foreign language and culture.

I think you can see the same thing with knowledge of foreign policy. It took a monumental horror such as 9/11 to wake the average citizen up to the necessity of becomming aware of world politics. Now is the time to improve this disasterously neglected section of the American education program.

Here's the issue. Look at the methods use to inform the sample population and get them to think "more about the issues":

- two days time

- carefully balanced (and publicly available) briefing materials.

- discussions in randomly assigned small groups led by trained moderators

- pose questions developed in the small groups to panels of experts and political leaders.

How do we adapt these methods to fit the general population? A real grasp of foreign policy requires all of these things because it requires a different method of thinking about issues. You can't just read a book, you have to discuss it. You have to look at theories and models of behavior and apply them to current events. You have to be able to understand what foreign policy makers are talking about. Basically, you have to learn a whole new language.

The question is, again, is this possible? Do people have the time? Will they make the time? Or do we literally have to start the education of foreign policy like we do everything else? Do we need Big Bird reading The Economist and discussing the results with the Count (who you know is a big fan of The Weekly Standard). Do we plan to have our children watch Scooby Doo and other cartoon guest-stars discuss the pros and cons of Realism vs. Constructivism? If we can have Bill Nye explain molecular interaction, if we can have a vampire puppet teaching arithmetic, then we should have a way of educating children about foreign policy.

The question is, again, is this possible? Do people have the time? Will they make the time? Or do we literally have to start the education of foreign policy like we do everything else? Do we need Big Bird reading The Economist and discussing the results with the Count (who you know is a big fan of The Weekly Standard). Do we plan to have our children watch Scooby Doo and other cartoon guest-stars discuss the pros and cons of Realism vs. Constructivism? If we can have Bill Nye explain molecular interaction, if we can have a vampire puppet teaching arithmetic, then we should have a way of educating children about foreign policy.For all the backwardness in the American awareness of foreign policy, it's still not as bad as it could be. Americans have access to more information about more places than almost any other population; they just choose not to look at it. They have more elections to vote in than anyone else. But quantity doesn't make up for quality, and we do need to improve that as best we can.

Friday, November 17, 2006

Democracy Done Right

One issue that comes to mind is the war in Iraq. It is not hard to imagine the U.S.’s political environment being the catalyst in the removal of U.S. troops from Iraq. Should politicians and the uninformed publics they represent be trusted with such a decision? Shouldn’t these decisions be free from the influence of politics? Will it be okay if troops are pulled out of Iraq because some politicians’ desire to be reelected?

The problem here is that the best part of democracy (the public’s ability to play a role in policy making) has become democracy’s weakness. The U.S. public cannot play a beneficial role in foreign policy formation when it has a demonstrated disinterest in countries and cultures other than its own. Certainly, the answer is not to have all the foreign policy making power concentrated in the hands of one person or a few people. The answer is not limited democracy, but educated democracy – if U.S. citizens are going to be a part of the foreign policy process, they ought to understand its basic concepts. Without getting into too many details, I believe this process starts with a reevaluation of curriculum taught in U.S. primary and secondary schools, and continues with broader and more informative press coverage (eg. Darfur instead of Tom Cruise).

Next Week's Readings

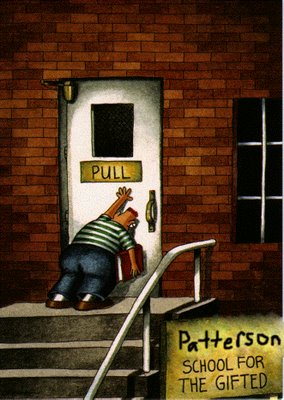

NB: at patterson prices, it's more expensive to print the pdf than to buy the book.

Thursday, November 16, 2006

What About Bob?

Deutch offers a cogent rationale for why Robert Gates is the right man and the right place and the right time for the Bush Administration. Basically, Deutch (a unique figure himself in the leadership roles he had in both Defense and the CIA) argues that Gates' intricate knowledge of the inner-workings of both the Pentagon and Langley make him the kind of cross-(bureaucratic)cultural animal we need after six years on increasing duplication of efforts between the Pentagon and the intelligence community.

"Perhaps nobody is better suited than Mr. Gates for reforming the military’s intelligence operations. The revamping of the government’s intelligence community in 2004 has been a mixed success. One important shortcoming is the Defense Department’s continued use of its considerable intelligence budget to run its programs in isolation from the other intelligence agencies.

Mr. Gates surely understands the need to integrate the military’s intelligence operations with those of other agencies. The Pentagon should stop competing with other agencies over collection and dissemination of information, and become more of an informed user of intelligence gathered by the multiagency intelligence community."

This point suggests Gates' relationship with the DNI will be crucial towards this end (isn't this what the DNI was supposed to accomplish in the first place?); however, to the extend that is true it seems Gates is uniquely well suited for that role.Wednesday, November 15, 2006

"let not thy left wingers know what thy right wingers doeth."

The good news is that we have an opportunity to use the perception of a shift in U.S. policy to try and get Iran, Syria NK to let down their guard a bit. Tony Blair's announcement on Monday contained severals significant points, among them:

1) There is now the possibility for a new “partnership” with Iran, if they cease supporting terrorism in Iraq and give up their nuclear ambitions. Along with Syria, they have to chose between isolation or cooperation.

2) Military action against Iran, as far as the UK is concerned, is ruled out

3) It is up to the United States to lead a new drive towards peace in the Middle East, entailing peace in Palestine and the LebanonWhat's significant about this is that it comes shortly after the earlier referenced announcement by the head of MI5, announcing the presence of some suspected 1200+ terror groups and 200+ individuals operating inside the UK. Tony Blair is saying this: if the U.S. is serious about defeating Al-Qaeda, they need to be as aggressive diplomatically with Iran and Syria as they are militarily in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Now, here's the problem. Blair is, as usual, calling on the U.S. for a sophisticated and intricate combination of military and diplomatic force. Unfortunately, there are doubts as to whether the soon-to-be Democratic majority in the House and Senate will be able to meet this challenge.

Firstly, we have Nancy Pelosi giving serious thought to backing John Murtha over Steny Hoyer for majority leader. He's hardly a good choice for a party who campaigned on changing "business as usual" practices in Washington and a sensible change in foreign policy.

Then we have her preference for Alcee Hastings over Jane Harman to head the House Intelligence Committee. Especially with Bob Gates' nomination for Secretary of Defense and the potential drift within the Pentagon towards the shadow side of the intel world, we need somone serious on the Intelligence Committee. Hastings seems like a very poor choice.

Neither Hastings nor Murtha possess the competence, credibility, or experience needed to meet Blair's call.

Hezbollah in Iran, Al-Qaeda and other Islamist militants are watching the US politics very closely. They've already made it clear that they intend to exploit the domestic transitions within the U.S. They're going to read very heavily into whatever happens, and if Pelosi pushes for Murtha and Hastings, it will send the following message: the U.S. is losing it's will to fight. Hezbollah and Al-Qaeda do not distinguish between "withdrawal", "troop reduction", "negative troop increases" or whatever you want to call pulling out of Iraq.

With two years left for the Bush presidency, the Democratic victories in the House and Senate, the retirement of Rumsfeld followed by the nomination of Bob Gates as Secretary of Defense, and the formation of the bipartisan commission on Iraq headed by James Baker, its obvious that the U.S. has the desire and the opportunity to change the way it conducts the war on terror.

And it's a good time to try a new plan. Rumsfeld's resignation marked the end of a certain phase in Bush's war on terror. Regardless of how many errors have been made, Saddam and the Taliban have both been overthrown, significant flaws in military organization and planning have been exposed, and the U.S. has demonstrated to the world that it can do more than blow up empty aspirin factories. Right now, the next move is ours. Our enemies and allie are waiting to see what we'll do next.

But there is probably a very small time window in which to decide on that new course, before our enemies decide to make the first move of the next round.

Monday, November 13, 2006

Saturday, November 11, 2006

Perplexions and Perceptions

We are only in the first few days after the election, and yet we have already seen some significant indications that the perception of the U.S., the war on terror, and the occupation in Iraq is changing. We have Iran's Khameni coming out with the following statement:

"This issue (the elections) is not a purely domestic issue for America, but it is the defeat of Bush's hawkish policies in the world," Khamenei said in remarks reported by Iran's student news agency ISNA on Friday.Then we have Al-Qaeda's Abu Ayyub al-Masri identifying politics in the US with American cowardice and weakness:

"I tell the lame duck (U.S. administration) do not rush to escape as did your defense minister...stay on the battle ground," he said.There is a growing concern, put forward in an article found here comparing the election to the Vietnam's Tet Offensive, that Al-Qaeda efforts to disrupt elections in the U.S. have been more successful than their attempts to disrupt elections in Iraq. This is not entirely true. Yet there is no denying that Al-Qaeda's activities - chronicled dutifully by the free press - strongly contributed the American electorate's dissatisfaction with the way the Iraq war has been proceeding.

It's probably no coincidence that the director-general of MI5 announces on November 11th that there are over 200 groups and 1600 individuals under observation. There is a definite attempt to counter the image of a weakening Western resolve.

The image of terror groups has always been their strength, since it takes considerable motivation for a democratic nation to agree to contribute money, lives and resources to combating a transnational organization. Are they freedom fighters, opposing Western offenses to their sovereignty? Are they simply terrorist fanatics, dedicated to destroying all things Western? It can be argued that the success of the war on terror depends significantly on the perceived power of the actors fighting the war. It is essential that the U.S. appear resolved to commit the neccessary money, technology, time, lives and military strength - to track terrorist support groups, monitor cash and weapons transactions, to predict and prevent attacks, etc.

Does the perception of the election and Rumsfeld's resignation pose a problem for the war on terror? Can this lead to an increase in casualties in Iraq? Will this contribute to the likelihood of another bombing in Europe? And if this is a threat, how do we counter it? It perception is a weapon, how do we wield it?

Friday, November 10, 2006

I've got no time for you right now

Now, G3, most of the things you mentioned I've discussed, one way or another, in my reply to DDN's comment to my post below.

We seem to be talking past each other entirely; so there's no point in continuing. For example, I've really tried not to talk about "Justice" too much (though I did use the word in linking to the story of a tortured detainee who can't talk to his lawyers because he may have gained knowledge of torture techniques. Ya think); I've concentrated on procedural flaws (show trial, killing witnesses and lawyers, little things like that) and the philosophical underpinnings of the theory of the state's power. Neither of these are relevant to the content of the crime.

But you say it's all about justice and demand blood. We're speaking different languages, and we're not going to get anywhere.

So I quit.

Thursday, November 09, 2006

Living in a world where rocking horse people eat marshmallow pies...

My Dear Mr. Cooke-

Time is short; please forgive my abbreviated style:

1) Yes, death is absolute; so what? I agreed with your point of degrees of difference (I think I did, and if I didn’t, I should have). The societal punishment spectrum runs from parking tickets, to prison, to a short walk off a tall gallows. If you’re arguing that the state shouldn’t have that last one, first prove why it’s bad. Again, we return to the simple issue that you don’t like the death penalty (if I’m reading you correctly), ergo society shouldn’t impose it.

2)

3) Your argument on the inability of execution to mete out proportional justice is preposterous. The most extreme punishment society can inflict is death (see point 1). Saddam deserves

4) Since you say you’re having trouble with the critical reading portion of our exam, allow me to simplify my already condensed argument: societies can and should inflict their most severe punishments on their most severe transgressors. Again, you seem to favor removing the “death-screwdriver” from the toolbox of justice (that last metaphor is now copywrited). Not liking the death penalty is not the same thing as proving the trial is a failure.

5) “I didn't go in to a litany of his crimes, or a rhetorical condemnation, because it's not relevant.”- Wrong. This is an argument concerning justice; one of the first rules of the Western legal tradition is ‘let the punishment fit the crime.’ In order to determine the appropriate punishment, we have to address the crime. Can you do that without mentioning the things he’s done? Since you brought in the ‘Reducto Ad Hitlerum' debate, let me ask: can you talk about an appropriate punishment for Nazis without mentioning the Holocaust?

6) Your criticism of the trial is still hair-splitting, deal with it. ‘International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights’? Why, I remember when I was little, my dad encouraged me to memorize the ICCPR. Yessir, many is the time he asked me: “Geriatric, what is Article 16?” And I’d respond, “Any propaganda for war shall be prohibited by law.” Well, ole Dad was a bit of a disciplinarian, and he’d crack me with an electrical cord for a while. Eventually, I’d figure out my mistake and cry: “Article 16 states that ‘Everyone shall have the right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law.’” My ole Dad, what a kidder!

7) You added a pile of citations toward the end directing me to sites that also don’t like the death penalty. (See points 4 and 1 above) According to Amnesty International, only 88 have abolished the death penalty for all crimes while 109 retain it, especially for war crimes. Europe can cuddle prisoners in time-out all it likes; most of the world, including

8) Cheeky Jihadi is good, but it could use some pizzazz. How about: Big Bob the Ba’athist, or Ali the Adorable Saddam Ally, or my (Arabized) favorite: Ibn Kook and the Good-time Marching Mujahadeen.

We're all trying to change your head

The Mao isn't really related, other than the fact that all political power (not just Saddam's) comes from the barrel of a gun, but I figured what the hell. This blog needs a little color.

Anyway, G3:

More to the point, you claim: “Execution is an exercise of absolute state authority, in a way that taxes or gun control simply aren't.” That doesn’t quite satisfy, does it? To use your own language, taxes and execution “are different in degree, not in kind.”

I'm not sure what to make of that; perhaps we need to start from first principles.

Death is absolute.

Do we agree on that?

Because if we do, then any difference in degree is a difference in kind.

But if you base your political reasoning on the assumption that death isn't absolute, or if you think that death and parking tickets are in some meaningful way comparable, then I'm not sure there's anything we can talk about here.

You fault my choice of dictionary, and point out the OED. Well, the OED definition is ass-backwards and formalistic. Under their definition, and your use of it, Iran isn't a totalitarian state. More than one political party? Get out of jail free.

The definition I used focuses on the behavior of the state and the authority it exerts over its subjects, which is a more productive way of classifying governments.

You ask if imprisonment is a fair, proportional punishment. What are you going to do, kill him a hundred thousand times over the course of the next 24 years? No punishment can be fair or proportional to crimes so severe. I didn't go in to a litany of his crimes, or a rhetorical condemnation, because it's not relevant. For the record, then: Saddam is bad. So was Mao, who I've thrown in for no good reason; so were Hitler and Stalin, who you used in preposterous non sequiturs. It's obscene to require everyone to prove their Saddam-hating bona fides every time he's mentioned; it's false piety to imply that only those who hold your position -- any position -- respect human life.

As far as ignoring your argument, I'm not sure what you mean, because I'm not sure if there's an argument in there. The closest I can come to drawing a thesis from your first reply's various rhetorical points is that, while Americans like due process, it's a preference that can be put on hold like Christianity when the crimes are severe enough.

That may not be what you mean, but it's my best guess.

Needless to say, if that's what you argue, I don't agree; due process, or for that matter Christianity, are to be tested in extremis, not there abandoned. If we don't live by our principles, they aren't really our principles. They are a sham.

G3 and DDN both accuse me of requiring something like "100% justice" or a "100% perfect trial." If you think I'm splitting hairs here, and that we're talking about the difference between 99% and 100% justice; I'll only point out that 4 participants in the trial have been killed for their roles; that several judges have resigned out of fear or political pressure; that the law establishing the court does not require proof beyond a reasonable doubt, but only "to the satisfaction of the court"; and that since the CPA order that established the Tribunal required it to comply with international standards, any of the items I've listed is sufficient to place the Tribunal in violation not only of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights , but of its own establishing law.

The tribunal, the trial, and the verdict were as poorly done as every other bit of the Iraq war and occupation. The inadequacies of the Tribunal leave open the possibilty of charges of a show trial; the sentence of death alienates the international community and our allies in europe.

You wouldn't think it would be possible to screw up convicting Saddam Hussein, but that's what we've done.

By the way; keep the insults coming; it's actually pretty amusing. I may even change my blogger handle to "cheeky jihadi."

Wednesday, November 08, 2006

Election Results - Happy Birthday Osama!

On a more serious note, every Democratic victory speech contained at least one sentence like "The American people have voted for a change" or "a new direction" or "something different". Soon-to-be the first female majority House speaker Nancy Pelosi mentioned in her own victor's cackle last night that there would be a change of direction in Iraq.

In light of this, let's return to the question posed earlier as to whether or not a Democrat-majority house is going cause any significant changes in Iraq. And keep in mind that this includes changes brought about by other nations/groups, who might react to news of a Democratic victory linked to the idea that the American public are dissatisfied with Bush and the Republican party.

To be perfectly honest, I'm more interested in the latter right now. I honestly don't think there's going to be a lot of Democratic initiative to radically transform the current policy in Iraq. We're not going to withdraw, but now it'll be harder to increase the troop number. Heck, the only two exerpts from Pelosi played on the radio mention "changes in Iraq" right after a promise to increase minimum wage.

Latin America's reaction will be very interesting to watch. Keep in mind that Daniel Ortega was confirmed as President of Nicaragua. If you've heard that name a lot recently and wondered who he is - look him up. If we had Chavez pleading with Americans to impeach Bush and read Chomsky before, now we'll probably have him demanding Cheney's balls on a plate and reading Shatner's Tekwar.

Someone is going to announce that terrorists have promised renewed attacks. UBL himself may release another late-night Jihadi infomercial - hell now that the Democrats are in power he might even show up on the Daily Show.

Now, what about China or North Korea? Iran?

And here's one final question. If Democratic countrol of the House, and possibly senate, leads to decisions even more unpopular with the American public than the (until January) current Republican incumbents, what sort of effects will a conservative backlash have?

Tuesday, November 07, 2006

Ortega II: The Rise of The Marxists?

Taking a timeout from Saddam-talk for a second (My two cents: the rest of his life spent in solitary confinement, followed by an eternity in hell, is more of a punishment for a man who spent the last 25 plus years in extreme luxury than a quick death at the gallows), I'd like to return to the topic of Marxism returning to the Western Hemisphere, and most importantly, why it isn't a big deal.

Firstly, it is important to point out that Ortega appears to have been democratically elected. So, I don't want to hear anybody bitching about him getting elected. Secondly, Ortega's election has no implications on American national security. The USSR doesn't exist anymore, so there is no fear that Nicaragua will be a launching pad for ICBMs. To be upset that leftists have come into power is sooo Cold War. Ortega himself has said that, while he is still a leftist, he no longer considers himself a Marxist--but a pragmatist. He even chose a political opponent as his running mate. The NY Times reports that his election seems to be as much a result of blowback against the corrupt former regime as anything else.

What type affect this could have on the US, if any, is in economic terms. I'm not well-versed in how the Nicagaruan government operates, but maybe Ortega's ascenion could result in the Nicagaruan government pulling out of CAFTA and future trade deals? The people of Latin America see on the one hand some countries in their region fairing poorly with free trade (Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia), but on the other hand have seen just as many countries succeed with it (Chile, Brazil, Columbia, Costa Rica). Maybe Nicagurans are ready for a new approach. I don't think walking away from free trade deals is the right way to go, but they'll figure that out by themselves.

Lastly, who cares if he has support from Hugo Chavez? Recent elections in the Andes and Central America have shown that Chavez's support is just as often a "death kiss" as it is helpful. I'd be willing to vote for Ortega based on the simple fact that Oliver North took the time to campaign against him.

You ain't going to make it with anyone anyhow...

My Dear Mr. Cooke:

In terms of summarizing your argument in a word, I can’t decide between adorable and cheeky. Not only did you ignore my reasoning, you introduced an inaccurate definition with this Merriam-Webster business. Had you bothered with the authoritative dictionary, the Oxford English Dictionary, you would have found: “A. adj. Of or pertaining to a system of government which tolerates only one political party, to which all other institutions are subordinated, and which usu. demands the complete subservience of the individual to the State.” I agree that a two party system makes us less exciting to watch, but it also negates the possibility that we are totalitarian.

More to the point, you claim: “Execution is an exercise of absolute state authority, in a way that taxes or gun control simply aren't.” That doesn’t quite satisfy, does it? To use your own language, taxes and execution “are different in degree, not in kind.” I think a debate on the death penalty is something worth having, though I’m not certain if this is the appropriate forum for it. Let’s try and focus on the case at hand:

Do you agree that crimes against humanity are in a category somewhat more severe than the common criminal? Evidence is easily available for the former, though the latter is oftentimes mired in doubt or dubious police tactics. There is a fantastic argument against capitol punishment for common criminals; it doesn’t persuade me, but it’s a valid argument. Saddam didn’t kill his wife’s lover while in the heat of passion nor did he steal a television from Sears; Saddam decimated generations. Keep your eye on the ball, my friend.

If proportionality should be a guideline in meting out punishment, what is an appropriate response to genocide, using chemical weapons, and wasting a nation over a 24 year period? I simply don't understand how jail-time is a fair way for Iraqis to show their disdain for Saddam's crimes. Sometimes, with appropriate evidence and appropriate aggrievement, states can and should decide that the actions of an individual are so egregious that they only proportional response is death.

Saddam’s guilt is beyond the shadow of a doubt; he videotaped many of his crimes, bragged about them, and used them to subdue his populace. Saddam, ever the legal scholar, has confined his complaints largely to procedural matters and screaming exhortations. Was his trial 100% perfect? No, and what trial is? The fact that he received a trial at all is remarkable in a state embroiled in civil war with only the tatters of government. Hell, when Saddam came to power in 1979, he did so personally at the barrel of a gun. Where is your concern and compassion for this? When I read opinions criticizing the trial, I can’t help but note a lack of commiseration for his millions of victims. Critique at will, but at least acknowledge the man’s crimes.

Monday, November 06, 2006

Count me out

You say that my objections are useless, and the real question is whether international and Iraqi law allow the court to sentence Saddam to death. You've got it ass-backwards. From a practical standpoint, it doesn't matter if the legal right exists. What, are EU troops going to extradite the judges to the Hague and put them on trial? What matters are issues of perception, and while I agree that the court system is a brave exercise in creating Iraqi institutions, it could certainly have been done better. Sentencing Saddam to death without an actual verdict, and not requiring proof beyond a reasonable doubt, lowers the percieved legitimacy of the trial.

2. Execution=taxes=gun control. Riiiight.

What is totalitarianism? Here's a not-bad definition, from Merriam-Webster:

Main Entry: to·tal·i·tar·i·an·ism

1 : centralized control by an autocratic authority

2 : the political concept that the citizen should be totally subject to an absolute state authority

You can't, in any logically consistent way, support the death penalty without agreeing to the concept in part 2 above.

Execution is an exercise of absolute state authority, in a way that taxes or gun control simply aren't. Death is absolute.

If a state claims or exercises absolute authority over its subjects, then it's a totalitarian state.

If a state does not claim or exercise absolute authority over its subjects, then it's not a totalitarian state.

There are a lot of things totalitarian states do that other states do, too -- send mail, build roads, shoot fireworks on national holidays. What makes a state totalitarian is absolute state power over its subjects.

On a side note, did you just quote H.L. Mencken for moral authority? Niiiice.

And if you do, in fact, "want to see the plan," the Human Rights Watch link provided a few posts ago has some decent ideas on how a better-structured trial court would have looked.

A National Security Breach

Several Los Alamos police officers were dispatched to a trailer park in New Mexico last week expecting to find a domestic dispute. The police entered the trailor to find the makings of a crystal-meth lab. Dozens of items were taken with the police but none more disturbing than three computer storage devices.

On the memory sticks was more than 400 pages of classified documents from Los Alamos computers containing, among other information stamped SECRET- RESTRICTED DATA, data on nuclear- weapons designs. The trailor owner, Jessica Quintana, had recently been employed by a contractor and had been assigned to scan aging paper documents into a digital format.

Quintana had been granted a "Q clearance" giving her access to nuclear weapons designs. She was also able to override the security locks on U.S. Nuclear Weapons. While the hard drives are kept in cages (to prevent such an incidence) they are "rarely locked" and Quintana was able to access everything and take everything home with her. She claims she downloaded the info after a deadline forced her to work at home and had intended to destroy all evidence when she was done.

I read this article and asked if it was a joke. It is really possible for someone to download on a jump drive nuclear weapons designs and then leave the government facility? That is absurd. Does anyone else find it odd that a girl with this kind of security clearance was also growing meth? What kind of precautions are taken to evaluate individuals with security clearances? Clearly, she does not have the best judgement.

Is this, as the official states, one of the greatest national security breaches in decades? I will leave that to my much more intelligent classmates to answer...

Well, Mr Cooke, We'd all love to see the plan....

Mr. Cooke-

My friend, you're wrong; while capitol punishment is/was routinely practiced by totalitarian governments, many non-totalitarian governments also practice it. Stalin taxed his citizens; is

The way you’ve framed your argument creates a false-dichotomy of either siding with the shooter, Chief of Police in Saigon Lt. Col. Nugyen Loan, or a version of jurisprudence sans sang. Coy rhetoric is no substitute for logical thrust.

Further, due process is an American value and one of our core beliefs. This is precisely the reason that Americans were so repulsed by Eddie Adams’ Pulitzer Prize-winning photo from 1969. The suggestion that

We can all forgive a filched wallet or even a black eye, but it’s neither humane nor compassionate to ask a rape victim to forgive her violator; H.L. Mencken, far more eloquently than I, once noted, “But when the injury is serious, Christianity is adjourned and even saints reach for their sidearms.”

Iraqis should not suffer Saddam to live. Islamic law formulates such a proclamation with the simple, elegant dictum: “his blood is forfeit.” When you murder a village, either with a rifle or with a phone call, you’ve placed yourself outside the law’s protection. Saddam will hang for his evil deeds and both Democrats and Republicans can raise a glass to the final, sickeningly-justified snap of a tyrant’s neck. More importantly, so can his victims.

"Free Saddam!" Any takers?

1) The first is on the Law Library of Congress website, highlighting the specific legal concerns.

2) Then there's also Human Right's Watch excellent background on the trial's legitimacy from the standpoint of international law

More than any philosophical, but in this circumstance largely useless, questions about whether or not the undoubtably U.S.-supported Iraqi court has the moral authority to sentence Saddam to death, the real issue here is whether the court can legitimately sentence Saddam to death without breaking international and Iraqi law.

Calling the trial a "sham" or an "outrage against justice" may be a fine bit of rhetoric alongside Dean's "Yargh!" and the Jihadi's "Death to the West!", but it doesn't do anything to address the heart of the matter.

This is not a puppet court. They aren't taking him out and stoning him, shooting him in the back and decapitating him and kicking around the head. These are not Iraqis being forced against their will to testify against Saddam, and these are not Iraqis forced against their will to weigh his crimes, and these were not Iraqis forced against their will to find him guilty. The Iraqi people are undergoing a serious, difficult debate on what to do with the man who - all credit for employing bloody terror to maintain the calm aside - destroyed Iraq.

This trial is one of the few real instances in which the Iraqis have tried to reach out to America, Europe, the UN and the EU, to try and act as a legitimate nation with legitimate institutions, to incorporate the ethics and behavior of the global community into one of the most significant episodes in their nation's history.

There needs to be debate about the trial: honest, serious debate. But if anyone wants to make the claim that the Iraqi court does not have the right to sentence Saddam to death, they need to support that claim with more than some vague, relative notion of "justice" or a snip about the moral hypocrisy of the Bush administration. Such claims need to incorporate the Iraqi legal system and international law.

That's how informed Iraqis are trying to frame the debate. Yes, there are also many Iraqis calling it a joke, or the inevitable result of a court on the payroll of the American dogs; but those are precisely the comments you'd expect from a populace that still hasn't grasped the concept of the democracy that has given them, at a bloody cost, the right to determine their nation's future in governance and law. You saw it in the USSR: "Oh, a trial? That's when the government kills whomever they want, right?" This is precisely why the Occupation is failing. Because when it comes to actually educating Iraqis about all the ways they can constructively inform themselves and criticize the governmment, all we have are marines trained to kill and destroy. No one seems to pay any attention to the fact that there is an Iraqi legal system. No one seems to pay any attention to the fact that there is a prominent Iraqi national institution carrying out a very difficult task, and that's a damn good reason for Iraqis to think the trial is a sham.

But that doesn't make it true.

You say you want an execution...

Just three points.

1. While Saddam was sentenced to death, the actual verdict hasn't been completed yet, but should be issued later this week. As if this trial needed to look more like a sham...

2. Hurrying the sentence, before the verdict is actually ready, makes for convenient political timing. But I couldn't possible imagine the Bush administration deliberately perpetrating an outrage against justice.

3. The death penalty is totalitarian. The police execution in the photo above and the sentence-without-verdict in Saddam's case illustrate the point. There are states in which the sovereign holds the citizens' lives in his hands, and there are those in which the state does not have the legal authority to kill its citizens. The officer on the streets of Saigon, the farcical court in Baghdad, or the district court on North Limestone are different in degree, not in kind.

E.OFF

Although safety wasn’t involved here, the power industry is one that should be concerned about massive disasters, especially in Europe where so much of the power is nuclear. And of course, the event has implications and could raise concerns for us here in Lexington, since E.ON is our provider as well. That said, I am taking my stand with the high reliability theorists. The competition fostered by decentralization, especially in the power industry, should typically result in fewer accidents as there is the added pressure on the power suppliers to not only provide power, but to provide power more safely and regularly than their competitors.

just a note...

Guilty

Had this taken place after everything had been set in stone: Saddam's outbursts would not have been tolerated, (he would have been gagged, or just his council show up), there would not have been a change of judge in mistrial, nor would the actions of his council been tolerated. One must look at their process as an adolescent graduating to the next level. They have shown they can handle themselves in judicial contexts, now they must improve upon it in hopes of ironing out the wrinkles.

With this verdict, we should expect an upsurge in violence. Especially after his death sentence has been carried out. We hope that the perpetrators of this violence finally realize that Saddam will not be returning and they must join Iraqi society or leave it. It is not beneficial to them to continue committing acts of violence by killing their fellow Iraqis.

What would have happened if Saddam was found innocent? Would he have been shot by a sniper, or someone in the crowds as he walked out? (I would like to think so, and would almost expect). Would he have been welcomed by the people? Would there still be an upsurge in violence? These are questions that we will never know the answers to and it is for the better. There is enough of a problem now with the insurgency and other violence in the Iraq, if Saddam was set free, this would only grow. It would be the confirmation they needed for their cause.

The Catholic Church believes he should not be put to death. Though I agree that every life ahs meaning and should be valued, there are calls for exceptions to be made. This is one of them. When someone has done the evil that this man has done, there is not a place on this earth for them. It would serve the greater good by putting him to death. Not just by punishing him for his evil deeds, but to get rid of the light at the end of the tunnel for the Iraqis who are committing these acts of violence in hope that one day Saddam will return.

Sunday, November 05, 2006

Saddam found guilty

2 of Saddam's seven codeffendents will join him at the gallows. More than that, though, one can hope that a lot of the more anti-American (rather than pro-Iraqi) sentiment will die with him.

Was the trial perfect? No. If Saddam had been an average citizen in any Western country, and his trial had gone on with the outbursts, assassinations, mishandled documentation and other courtroom indiscretions that plagued this trial, he would have been let off with a mistrial. But this isn't any citizen, and this isn't any case. This is Saddam Hussein. Iraqis know what he did. The world knows what he did. Iraqis will forgive the court if the trial was not 100% legitimate.

And furthermore, do not give too much credence to Saddam's last-ditch attempt to become a martyr. The only people who are really going to miss him are those who saw their survival as being dependent on his authority. So there will be some significant Sunni unrest in Tikrit and the rest of Saddam-Land. So what?

This won't fix all the problems in Iraq, but it will give the entire nation a chance to pause and ask themselves, "Now that he's dead, now what do we do?" It will encourage debate amongst Iraqis, serious debate. I don't know what the U.S. needs to do to make the most of it, but I do know what they have to avoid: letting Saddam live. There will be an appeal, according to Iraqi law, but no matter what happens the conviction must not be overturned.

Justice must be done, and this is the best opportunity the U.S. will ever have to show that Western justice and Iraqi justice are on one side, and the "justice" of the Islamists and of the Saddams of the world will always be on the other.

The article, for those who wish to read it: http://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/05/world/middleeast/05cnd-saddam.html?ref=middleeast.

I think I speak for many, when I say, good riddance. That being said, Saddam is a clever SOB, and no human life is without merit. But I think God will understand me when I say, I forgive him, but it's time for him to die.

Saturday, November 04, 2006

More NPT threats?

I couldn't help but notice that six, yes six, Arab states are beginning programs to develop nuclear technology, allegedly for peaceful purposes. The news report, linked from Drudge, states that the states want to use the technology for energy and desalination, but the proliferation of reactors in this area should, in my mind, be troubling. The states the article names are

Even if these programs are for peaceful purposes, allowed under the NPT, does this development have the potential to cause destabilization in the region(s)? The report notes that many of these states are worried by

Clearly, I think this forces the

Thursday, November 02, 2006

Some Irrational Thoughts on Rational Choice

Did we ever really answer Douglas' question as to how we evaluate current situation? It seems to me you can't ever really guess which model a country will follow. We know countries can change their grand strategies and ways of thinking so looking at the past can only really tell you what was done in the past. Sure if a country has stayed the course and has been 100% consistent it could help us- but does that happen?

As for rational choice, I think it's interesting to think of in terms of the American presidency. If Bush were up for re-election would we still be in Iraq letting things progress as they are? It seems to me a president might be more likely to pay attention to what's rationally right for the country he represents when he could stay in the White House for 4 more years. When you are not facing the campaign trail, perhaps you start to think more in terms of you and your best interests.

Wednesday, November 01, 2006

Unrelated News

...I probably have some reading that I should be doing...

George's "Multiple Advocacy"

Let's look at Alexander George's "Case for Multiple Advocacy in Making Foreign Policy". The Iraq war is now far enough along so that we can apply the "Multiple Advocacy" framework to the information we now have about the deliberation process that led to our to stick our willy in the oil-rich hornet's nest that is Iraq.

There's no denying that something important happened when the President and his closest advisers decided to invade Iraq, expecting a populace teeming with latent ethnic tensions checked only by a brutal dictatorship employing every nasty trick in the book - including music videos. The most publicly debated concern is that certain important considerations were given insufficient attention - which is a nice way of saying that the decision makers overlooked some pretty important sh*t. Could this oversight have been prevented if there had been stronger representation for alternatives to the 2003 invasion of Iraq? The readings for this week are obviously centered around the fiasco of the Bay of Pigs, along with the near-fiascos of the Cuban Missile Crisis and the threat of annihilation posed by the Cold War, but we can at least use the George, Halperin and Allison's analyses to come up with some further questions regarding the Iraq War and future important foreign policy decisions.

I think the BoP was the best example of an uninformed president making a bad decision based on incomplete information provided by a group of men determined to carry out a certain plan - or an UPMBDBIPGMDCP scenario, in the foreign policy lexicon. What was similar, and what was different about the decisions regarding BoP and IW(the iraq war)?

For one thing, Kennedy didn't have Rumsfeld and Cheney - how much of an effect can "multiple advocacy" have when up against two undeniably strong and skilled bureaucratic grapplers? For another thing, BoP was a US covert military action, where the Iraq War was (supposed to be) a multilaterial action sanctioned by the international community and in accordance with UN requirements for war. During last week's Iraq Roundtable discussion, the point was raised that when one sees such a plethora of reasons for going to war, one should ask why one good reason does not suffice, and whether this implies the absence of any good reason to go to war. I think that would be an excellent point...if the Iraq War hadn't required some sort of international support. How many of those reasons - humanitarian, national security, economic, etc. - were just for the US citizenry, and how many were for the international community? After all, the EU may not give a fig about some US domestic issues, but they might care quite a bit about a more general, humanitiarian objective.

Just a few thoughts on the matter, which is appropriate given how few thoughts were given the matter in the first place.

It's all in your mind...

In "Conceptual Models and the Cuban Missile Crisis" Allison discusses a plan for Marines to "liberate the imaginary island of Vieques."

So on behalf of my Puerto Rican friends, I'll point out that Vieques is real; that it's part of the US, and that by 1969 the US Navy had been trying for 20 years to deport the natives and use the entire island as a gunnery range.

The Navy ended up getting the boot instead, but it took another 35 years.

http://www.vieques-island.com/

Saudi Nuclear Mania

Why isn’t

King Abdullah knows quite well that his kingdom has been in continuous competition with Iran since 1979 for the hearts and minds of the global ummah. While Abduallah's predeccesor, King Fahd, busied himself in funding radical Islamist madrasahs in

At the same time, only 18 short miles separate